Prologue:

The Mechanism

Around Easter 1900, Captain Dimitrios Kondos and his crew of sponge divers from Symi stopped at the Greek island of Antikythera to wait for favourable winds. During the layover, they began diving off the island’s coast wearing the standard diving dress of the time – canvas suits and copper helmets.

Diver Elias Stadiatis descended to 45 meters (148 ft) depth, then quickly signalled to be pulled to the surface.

He described a heap of rotting corpses and horses strewn among the rocks on the seafloor.

Thinking the diver was drunk from the nitrogen in his breathing mix at that depth, Kondos put on his own diving gear and descended to the site. He returned to the surface with the arm of a bronze statue.

Shortly thereafter the men departed as planned to fish for sponges but at the end of the season they returned to Antikythera and retrieved several artefacts from the wreck.

Kondos reported the finds to the authorities in Athens, and Hellenic Navy vessels were quickly sent to support the salvage effort from November 1900 to 1901.

Together with the Greek Education Ministry and the Royal Hellenic Navy, the sponge divers salvaged numerous artefacts. By the middle of 1901, divers had recovered bronze statues, one named ‘The Philosopher’, another, ‘The Youth of Antikythera (Ephebe)’ of c. 340 BC, and thirty-six marble sculptures including Hercules, Ulysses, Diomedes, Hermes, Apollo, three marble statues of horses, a bronze lyre, and several pieces of glasswork. Many other small and common artefacts were found and the entire collection was taken to the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

The death of diver Giorgos Kritikos and the paralysis of two others due to decompression sickness put an end to work at the site during the summer of 1901.

On 17 May 1902, archaeologist Valerio Stais made the most celebrated find while studying the artefacts.

He noticed that a severely corroded piece of bronze had a gear wheel embedded in it and legible inscriptions in Koine Greek.

The object would come to be known as the Antikythera Mechanism.

Originally thought to be one of the first forms of a mechanised clock or an astrolabe, it is now referred to as the world’s oldest known analogue computer.

Although the retrieval of artefacts from the shipwreck was highly successful and accomplished within two years, dating the site took much longer. It was speculated that the ship was carrying part of the loot of General Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix 138BC to 78BC (latterly named Epaphroditos, Favoured of Venus) from the successful Roman siege of Athens in 86BC and was on its way to Italy.

A reference by the rhetorician Lucian of Samosata to one of Sulla’s ships sinking in the Antikythera region gives credence to this theory and coins discovered on the wreck in the 1970s were found to have been early Roman.

In 1974, Professor Derek de Solla Price of Yale University published his interpretation of the Antikythera Mechanism.

He argued that the object was a predictive, analogue calendar computer. From gear settings and inscriptions on the mechanism's faces obtained by X-Ray imaging, along with the relatively new science of carbon dating, he concluded that the mechanism was made prior to 87BC and lost shortly afterward.

Foreword

Wandering the back streets of a southern French village one warm summer evening, we came across a row of terraced cottages beside a river.

Two of the occupants, both elderly ladies, were sitting outside on their doorsteps. We exchanged nods, that being the extent of my French, and walked on until I stopped at one particular house.

The curtains were open as was the door and, although the light inside was very dim, it was reflecting from the dials of many clocks of all sizes.

This image was to become the house of Auguste Godenot.

The river beside the houses was not much more than a dry bed but there were many signs that on occasion it could be much more than that.

We suggested that it might become ‘a torrent in winter’.

This became my first working title for the book.

Around this time I became aware of the Antikythera Mechanism through a magazine article. It absolutely captivated me in a way that few things do. I still find it astounding that medieval civilisations lost the artistry to create such intricate aids as this, given the trouble that the initial investigation of it caused, namely to Valerio Stais, its discoverer.

He was labelled a hoaxer and allowed to go to his grave with that as an epitaph before the emergence of the truth.

The thing that caused Stais a problem was the discovery, by early X-Ray, that the mechanism contained a differential with a planetary gear system. These systems were not thought to have been invented until at least fifteen hundred years later.

Carbon dating, shortly after its invention, restored its validity to the date of 86 B.C. and also to Valerio Stais’ reputation, although many years too late.

I began to wonder what would happen if there were more than one Mechanism. Would a machine such as this have the capacity, in the right hands, to do more than calculate? Perhaps it could also predict. Even if that were no more than a possibility, how would the powerful react to the potential of that. One can only imagine the advantage it could create.

For this novel, imagining that is exactly what I did.

In the 2010’s we drove many miles around Europe and the idea for this story followed me wherever I went.

The picture was slowly building inside me all the time I was there and has continued up until today as I write this. I don’t think there has been a moment since that warm summer night that this idea has left me entirely alone.

As the story began to build in my imagination and across the page, I realised that it encompassed more than one timeline. In fact, there are many. You will need to read this book and Volume II, ‘Argo Navis’, and Volume III, ‘Ophiuchus’, to discover all of them. They are not of necessity sequential, but I hope the links make them emotively so.

When the writing of this first Journal was almost complete I realised that I had the opportunity, while attending a wedding in Certaldo, Italy, to personally visit all the other places across Europe that my protagonists visit in the book.

We varied our route home to encompass Val de Susa, Italy, where we found a beautifully decorated Monastery which became the Abbazia. We have walked along the platform of the Stazione in Susa. We have heard the incredible roar of the waters at Rheinfall am Main, and traversed the Lötschberg tunnel. I became locked in a restaurant toilet above Frutigen and was forced to telephone my way out. We have stayed overnight at the Hotel Rugenpark, Interlaken, (and in here have made an accurate description of it as it was then), taken coffee at the Altstadt Tearooms there (without arsenic, so it couldn’t have been a Friday) beside the raucous turbine grind of the Elektrizitätswerk. We have sailed Thunersee on a paddle steamer and experienced all the European points in the book but, the main event, although not on the same tour, was our later trip to Athens and Antikythera. That journey is a complete story in itself and for that, you will need to find…

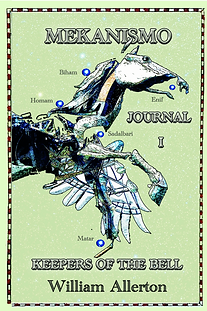

‘Mekanismo’, Journal II, ‘Argo Navis’

(Cybermouse Books 2024 ISBN 978-1-0686097-1-8)

I hope you enjoy this first part of the story and the places and times it takes you to.

Best Wishes,

Bill Allerton

Read the 1st. Chapter HERE